Why do you buy what you buy? Is it always for the right reasons? Are you a rational shopper? I asked these questions of the audience in a recent talk I gave on my new book, Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters. Most of the people there said they used logic and reason to make thought-out shopping decisions. Perhaps you think you do as well.

Unfortunately, research suggests we overestimate our logical purchasing. We make many irrational decisions, in shopping and other areas, that are shaped by our external context—the environment created by salespeople, advertisements, store and website layouts—rather than our internal self-directed goals.

I dug deeper with the audience on just one of many types of shopping decisions driven by instinct rather than reason: impulse purchases—when you give into the temptation to buy something driven by a momentary gut reaction. Websites often use exit pop-up ads to entice impulse buys and retail stores have the most impulse-inducing goodies by the registers. With this specific question, many audience members acknowledged making a recent impulse purchase, one they wish they wouldn’t have made.

Have you had such experiences recently? We all overestimate our ability to restrain our impulses, a tendency that cognitive neuroscientists and behavioral economists like myself call restraint bias. The restraint bias is one of over a hundred mental blindspots that scientists call cognitive biases, which cause us to make bad choices, in shopping, relationships, and other life areas.

People Who Think They’re in Control Are Often the Most Impulsive

Research on the restraint bias shows that people trying to quit smoking who had an excessively high opinion of their impulse control opened themselves up to temptation too much, resulting in higher rates of relapse.

Such research, while done on Americans, has been confirmed in studies in global contexts as well. Scholars in India have found poor impulse control correlated to impulse shopping.

A new online survey by Top10.com provides further evidence for the impact of context rather than our internal drivers and goals on our shopping choices. The survey asked a representative sample of over 1,000 Americans about how often they made impulse purchases, how frequently their shopping decisions stemmed from something they recently learned, and how often the setting shaped their purchasing choices.

People usually under-report their behaviors in answering such questions, especially in social settings, because it feels embarrassing to acknowledge their own poor decision making. I suspect that’s why it took some nudging to get the audience in my talk to acknowledge the impact of external cues in their shopping decisions.

Even when answering online surveys, respondents are reluctant to admit to bad shopping decisions. Scientists have a name for this cognitive bias called post-purchase rationalization. This mental blindspot refers to us self-justifying and developing more positive feelings for shopping decisions after we made them, regardless of the quality of these decisions. Thus, the actual rate of external-driven shopping behavior is likely substantially higher than reported in the survey.

In the Heat of the Moment

Too many caveats, in your opinion? That’s because the survey results proved very surprising.

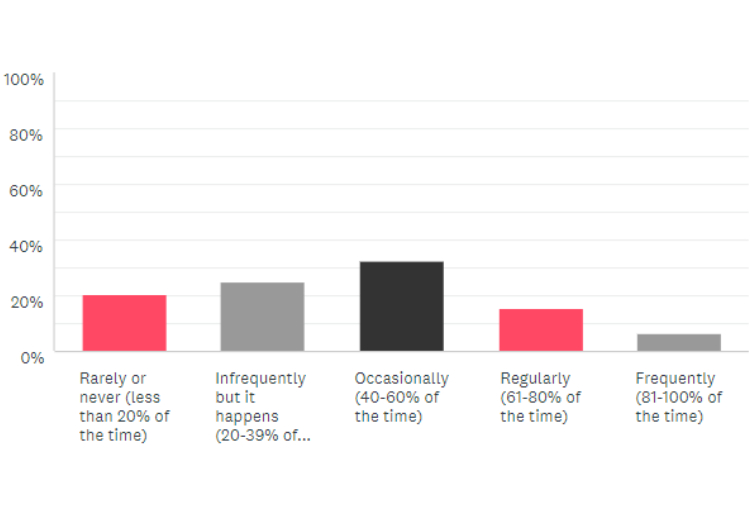

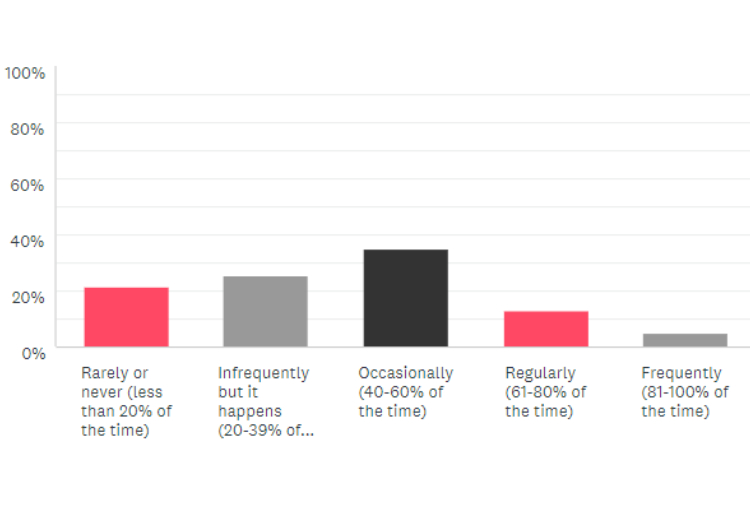

For example, when shopping in-person, only one-fifth of the survey respondents reported that they rarely or never make impulse purchases. Over half of the respondents said they make impulse purchases over 40% of the time they shop. Considering the negative connotations associated with the concept of impulse purchases, as evidenced by the many online articles about how to stop impulse shopping and even therapy programs devoted to this topic, we can safely assume that the reality is substantially higher.

These numbers characterize the large majority of purchasing behavior in the US, which still happens in-person. For example, the US Department of Commerce reports that in 2017, brick-and-mortar store sales were $3,043 billion, while Ecommerce was just $453 billion. Yet online shopping is rising faster than in-person sales, with a 16% increase in Ecommerce from 2016 to 2017 compared to a 2% increase for brick-and-mortar stores over that same period.

So how much impulse shopping do you think takes place online? Is it more than in-person or less? Are people more swayed by Amazon’s very convenient one-click buy option or by the very visceral display of candies by the grocery store register?

Decide what you think before reading onward. Now check out the graphs below from the survey, which tell the story quite clearly.

When Shopping In-Person, How Often Do You Make Impulse Purchases, as Opposed to Thought out Purchase Decisions?

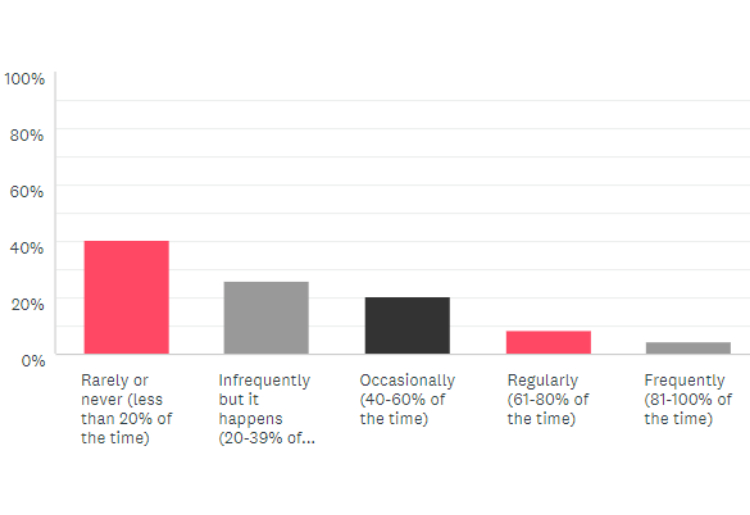

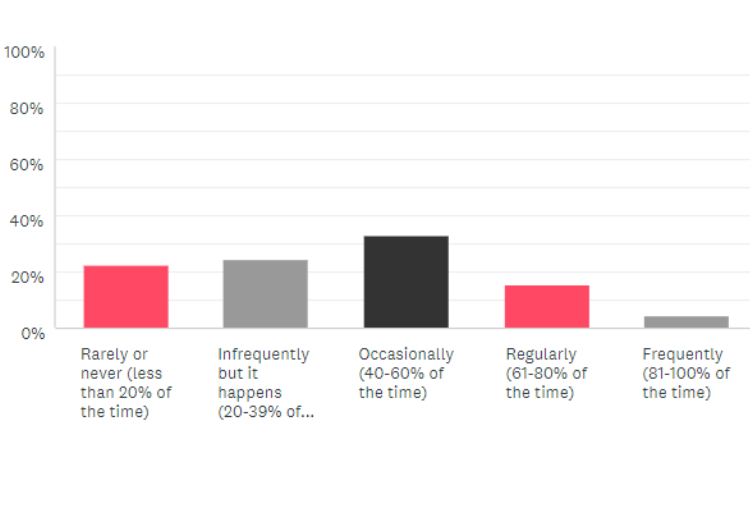

When Shopping Online, How Often Do You Make Impulse Purchases, as Opposed to Thought out Purchase Decisions?

Twice as many people minimize impulse purchases online, giving the answer “rarely or never” two-fifths of the time, compared to one-fifth for in-person buying. Just over a third report impulse purchases online over 40% of the time, compared to over half for in-person.

Again, these numbers are likely lower than reality, but given that we’re comparing the answers on the same survey, we can treat this enormous difference as credible. So if you want to avoid impulsive shopping, then shop online instead of in-person.

What Explains These Differences?

We know that certain factors move us to make impulsive purchases online. Research shows that online reviews often drive impulsive purchase behaviors, especially for people who focus on the pleasure they will get from their purchase. Unfortunately, many shoppers fall into dangerous judgment errors by trusting user reviews online. Bogus reviews are widespread. It’s easy to buy fake good reviews, and most people don’t take the time to learn about how to spot fakes.

Other factors that research finds strongly impact our likelihood to make impulsive online purchase have to do with website quality: the better we perceive the website, the more likely we are to make an impulse purchase. In addition, websites that are interactive and vivid increased impulse buys. Beware these websites if you want to minimize impulse buys.

Other factors decrease our likelihood of impulse purchases online. The vividness is limited to our eyes, hitting only 1 our of our 5 primary senses. Moreover, if we’re online, we can quickly compare the quality of an item we’re tempted to purchase, through looking at a shopping comparison website or—if there’s no other option—evaluating online reviews. We can also turn away from our computer or put down our phone to think about the purchase in a calm and reflective manner.

By contrast, in-person shopping minimizes the opportunity for comparisons, leaving is much harder, and—depending on the store—it hits our eyes, ears, touch, and sometimes smell and taste. We can’t underestimate the impact of the sensory vividness of in-store stimuli, which speak directly to our Autopilot System, the emotional part of us that motivates the large majority of our decisions. It’s the part that causes us to make impulse purchases, and our Intentional System—the rational and reflective part of us—often can’t stop the Autopilot System once it’s been triggered by emotionally appealing stimuli.

No wonder that research on in-person impulse shopping highlights the critical role of design and ambiance of stores on creating a positive emotional Autopilot System response as a means of causing impulse purchases. Likewise, salespeople who create a positive emotional connection between themselves and customers are more likely to get an impulse sale, and quality customer service has been found—across the globe—to lead to greater impulse buying. So did over-stimulating the senses.

Your Personality or Your Environment?

All the factors I described above as driving impulsive shopping, whether online or in-store, stem from context. Indeed, the only thing that can cause impulsive shopping is external stimuli. By definition, impulsive shopping involves purchases that go against our rational motivations, instead triggering our emotions to drive poor shopping decisions.

Ironically, the Top10 survey indicated that the respondents—just like the audience in my talk—lacked self-awareness of when they were driven by the context to make their shopping decisions. Impulse purchases represent only one of many types of context-shaped shopping decisions. That means the frequency of shopping decisions influenced significantly by the external context of the shopping environment—in-person and online—must be quite a bit larger than the frequency of impulse shopping decisions.

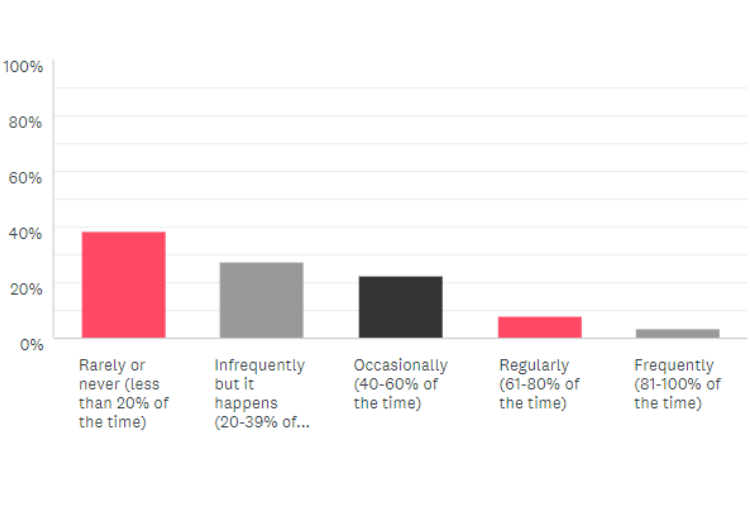

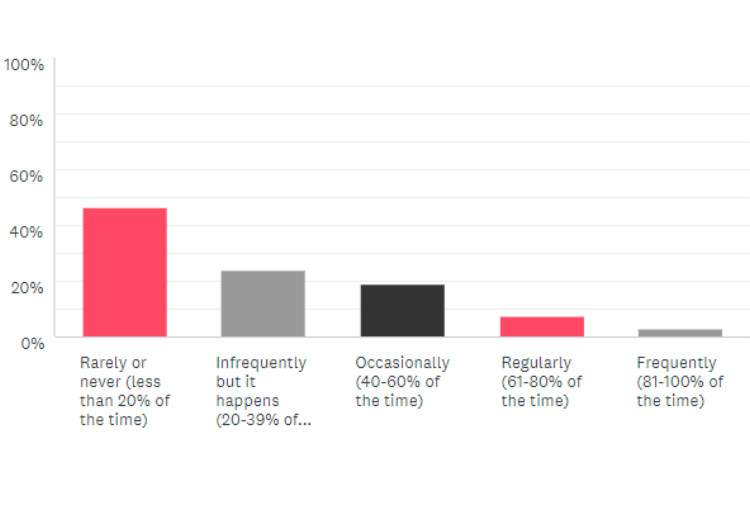

Yet when asked about how often they made decisions influenced by context, survey respondents reported numbers substantially lower than those they reported for impulse shopping. About two-fifths for both in-person and online shopping said they rarely or never made shopping decisions based on the context. Only a third acknowledged making in-person shopping decisions over 40% of the time, and less than a third for online shopping.

When Shopping In-Person, How Often Do You Make Purchase Decisions That Are Influenced by Your Context, Whether People Such as Sales Personnel or Other Customers, or the Physical Environment of the Store or Other Factors?

When Shopping In-Person, How Often Do You Make Purchase Decisions That Are Influenced by Your Context, Whether People Such as Sales Personnel or Other Customers, or the Physical Environment of the Store or Other Factors?

It’s About How It’s Framed

What explains this lack of awareness? One of the major culprits is the subtle but powerful cognitive bias known as the framing effect, our tendency to make decisions differently based on how the decision is framed for us by the context.

Say you walk into a store to buy a pair of shoes, and see a sign that says “get a pair of shoes for FREE, when you buy 2 pairs.” That is a tempting deal and you might go with it, even though you only intended to buy one pair originally. After all, you’re getting a free pair of shoes! You’ll wear the first pair out, and you’ll be all set with 3 pairs.

Imagine you walk into another store to buy a sweater, and see a sign that says “buy 2 sweaters, get a third FREE.” Now, that deal is less tempting. You have to pay for 2 sweaters, when you only wanted 1, to get the freebie. You’d rather pass, and maybe find another store with a better deal.

Or envision you’re buying antibacterial hand gel. One brand’s bottle on Walgreens.com says “kills 99% of all germs.” Another brand’s bottle says “leaves 1% of all germs alive.” Which bottle would you choose? You won’t be surprised that the vast majority would choose the first, even though both mean the same thing.

What gives? Our emotions—which are responsible for the large majority of our decisions—prefer the best-sounding, easiest route, and go with our first impressions. So the shoe store that offered you the free pair of shoes first, and only later stated that you have to buy 2 pairs, got an immediate positive reaction, compared to the sweater store.

Similarly, our Autopilot System feels good about the bottle that “kills 99% of germs” and focuses on that, ignoring the unmentioned but very real 1% of germs left alive. By contrast, the bottle highlighting the germs left alive causes our emotions to focus on that, resulting in a negative reaction that dissuades us from buying it.

Giving Too Much Weight to Things We Learned Recently

Notice that none of the cases above involve impulse purchases. You intended to purchase the shoes, sweater, and gel; the framing shaped your decision to buy or not buy, how much to buy, and what brand to buy. Both in-person and online stores have myriads of ways to frame shopping decisions in ways both obvious, such as store shelf placement, to subtle, such as Amazon using its algorithm to favor its private label products.

Another aspect of the environment we often ignore, to the detriment of our decisions, is our informational environment, whether from the retailer or from the external context. We often pay too much attention to something emotionally charged that we learned recently, especially negative information, a cognitive bias scientists call attentional bias.

For instance, whenever plane crashes occur, people tend to feel greater fears around buying plane tickets, and instead try to travel by car whenever possible. Unfortunately, they’re putting themselves into greater danger, since car travel is much less safe than flying.

Or say you hear about how avoiding gluten is good for you, and decide to stop buying products made with gluten, as so many people are doing right now. There’s no research basis for going gluten-free if you don’t have celiac disease, and scientists say that the large majority of people going gluten free are just wasting their money.

The impact of the context provided by attention-grabbing information comes through clearly in the survey. Only one-fifth rarely or never make shopping decisions based on newly-learned information. Over half use new information to guide their shopping decisions over 40% of the time.

When Shopping In-Person, How Often Do You Make Purchase Decisions That Are Influenced by Something You Learned Recently, Such as From Something Someone Else Told You, or Something You Read or Saw in Mainstream Media?

When Shopping In-Person, How Often Do You Make Purchase Decisions That Are Influenced by Something You Learned Recently, Such as From Something Someone Else Told You, or Something You Read or Saw in Mainstream Media?

What Can You Do?

Cutting-edge research in cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics shows that you can develop a host of mental skills to overcome the dangerous judgment errors that threaten you in shopping and other decision-making areas. The first step is to accept your own vulnerability to cognitive biases, and commit to taking steps to address them.

Focus on changing your context to minimize poor shopping choices. For example, you can choose to shop online more often to reduce the temptation of impulse shopping. You can also make a reflective and intentional precommitment to get your products in a specific manner, such as a subscription service, preventing you from making bad decisions in the moment.

Delaying decision-making helps decrease the power of the Autopilot System and increase the impact of your Intentional System for your shopping choices. So try to delay your shopping decisions by at least half an hour whenever possible, and ideally sleep on it.

Making a list of what you will buy, how much of each, and for how much, would also prove very helpful. It would be overwhelming to do so for everything you buy, so target either repeating purchases that you make regularly or one-time significant expenses above $100.

High-quality advice, whether from people you trust or reputable online sources, has been found to be effective in addressing poor choices. Determine quality sources and consult those in advance of making a shopping decision.

Avoid dangerous decision disasters by getting the article author's new book, Never Go With Your Gut

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky is a writer for Top10 and a scholar of behavioral economics and neuroscience. Called the 'Office Whisperer' by The New York Times, Dr. Gleb Tsipursky helps leaders improve retention and productivity as the CEO of the consultancy Disaster Avoidance Experts. He's also the best-selling author of several books, and was featured in over 750 titles in CBS News, Time, Scientific American, Psychology Today, Inc. Magazine, and CNBC.